People Who Print

- senicetak malaysia

- Nov 26, 2024

- 5 min read

by Dayang Aina

Community, collaboration, and the spirit of sharing are fundamental to the practice of printmaking in Malaysia. Even before institutional support, Malaysian printmakers have banded together through art clubs and societies since the early 1940s, following the arrival of woodblock prints from China. The students of Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts took these prints as inspiration to begin their own printmaking culture, using the backs of wooden ladles to rub ink into paper. The medium was finally formalised by academic institutions with the establishment of a teacher training course offered by the Special Teacher Training Institute (STTI) in 1962, where students were provided a humble printmaking workshop. Today, printmaking collectives continue to thrive, committed to making meaningful contributions to the development of creative communities in Malaysia.

Because of the steep cost of printing presses, high-quality paper, large working spaces, and other printmaking necessities, many Malaysian artists’ first encounter with printmaking occurs during their student days. In these shared studios, batches of aspiring artists are tested for their technical skill, operational know-how of equipment, imagination, improvisation, and, most importantly, patience. Only few continue printing after graduation, and even fewer choose printmaking as a major, perhaps because to choose this medium is to commit to an art practice complete with a variety of challenges. Consequently, this commitment to unpredictability often generates a particular type of artist, one that embraces obstacles as opportunities for both artistic and personal growth. Throughout this project, one word made an appearance in almost every conversation with these artist-printmakers: discipline. Regardless of their prior experience with printmaking, each artist emphasised the importance of discipline to the process, and it is seemingly impossible to produce one without it.

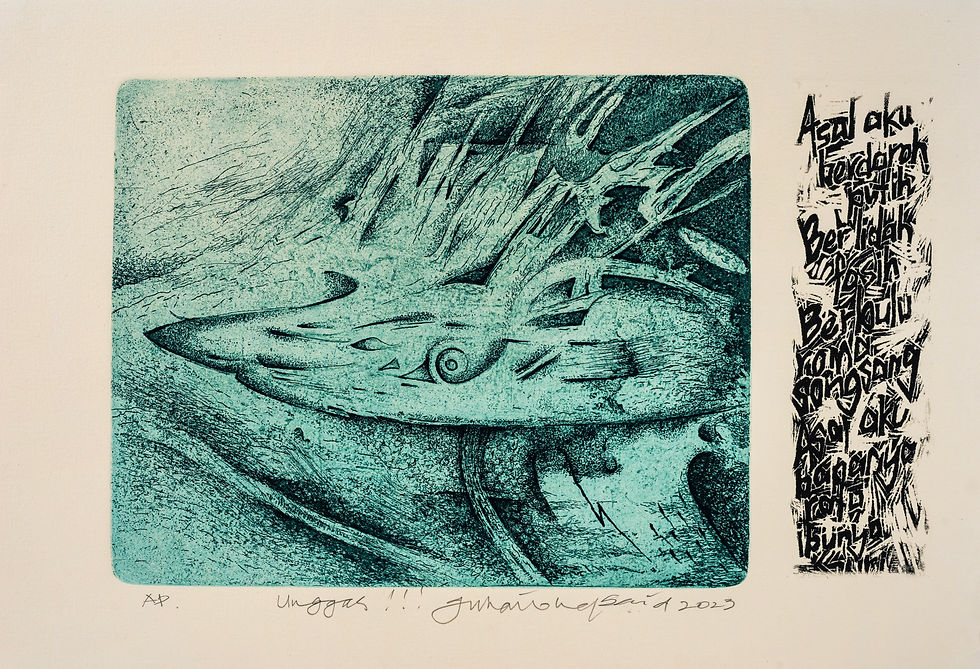

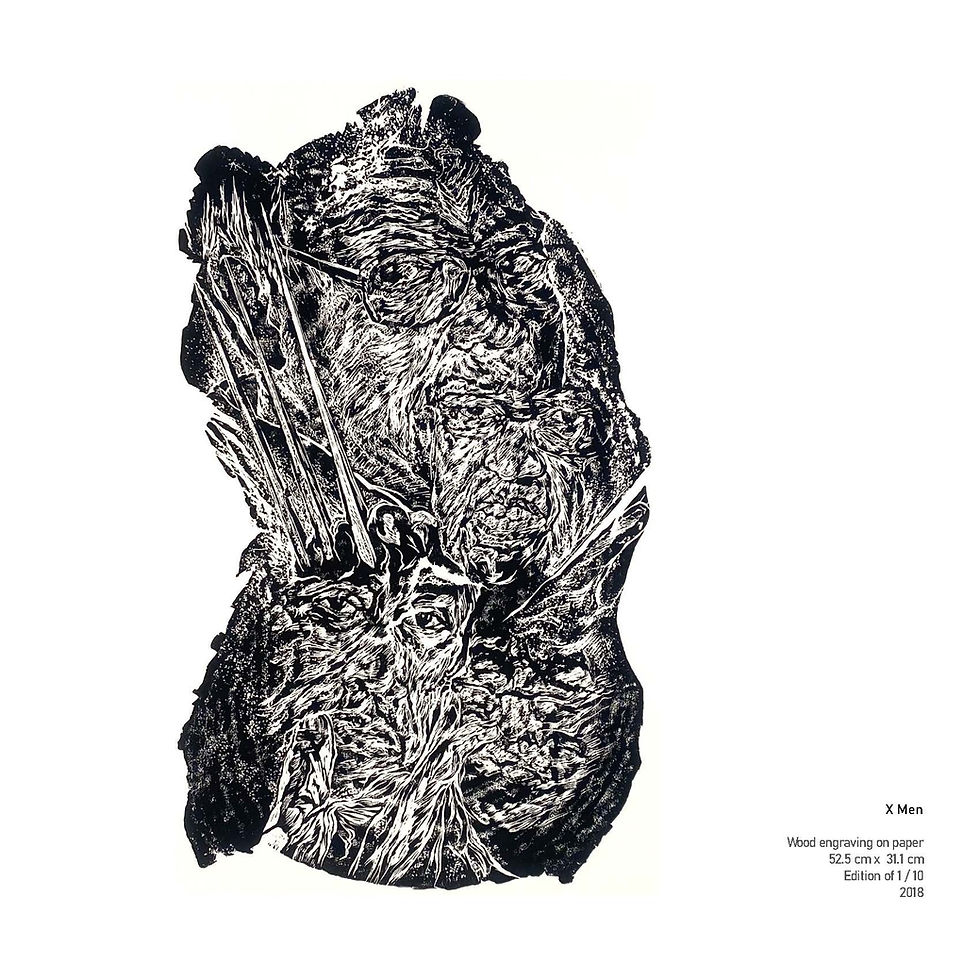

For those artists who eat, sleep, and breathe printmaking (namely Juhari Said, Faizal Suhif, Fadli Mokhtar, and Samsudin Wahab), this strictly regimented art practice is given full credit for the continuous development of their character. Clearly, they are artists who are serious about their work, but also about play. Initiated by Juhari, GoBlock is an artist collective who are committed to the development of both traditional and alternative printmaking since 2009. Together with key members Faizal, Fadli, and Samsudin, GoBlock embodies the communal spirit of printmaking, encouraging artistic exchange between each other, other artists, and their viewers. The group is known for expanding the definition of printmaking, continuously challenging its conventions in their exploration of all its aspects. Sabahan art collective Pangrok Sulap shares a similar attitude towards printmaking and community. The group is composed of like-minded artists, activists, and musicians, and is based in Kota Kinabalu and Ranau. Co-founded by childhood friends Rizo Leong and Jerome Manjat in 2010, Pangrok Sulap’s mission is to amplify the voices of marginalised communities through woodcut prints.

Jane Khoo and Rahman Mohamed explain this sense of collectivism in printmaking clearly in their essay, ‘Development of Printmaking in Malaysia’: “Printmaking is [...] communal in nature, and it encourages humility. Its end results exist in multiples, which enable them more affordable pricing. They are thus more easily circulated, while retaining a sense of originality through the presence of the artist’s touch.”1 This statement helps us reflect on the sense of community that is unique to this practice. Recognising the lack of local printmaking facilities, Samsudin, Faizal, and senior artist Bayu Utomo Radjikin opened Chetak 17 (formerly known as Chetak 12) in Melawati in 2017. Since its establishment as a communal studio and exhibition space, Chetak 17 has been run by and for artists, with the intention of elevating printmaking as a crucial practice. On the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur is Juhari’s studio, Akaldiulu, another multipurpose space that welcomes anyone who is willing to learn about printmaking as a way of life. It is in spaces such as these that artists and printmakers thrive, spaces conducive to the free flow of ideas amongst other practitioners who find the same joys and challenges in the art form. These exchanges can be as formal as workshops and as informal as weekly art jams–either way, it is the value that they place in their community that enriches their individual practices.

1 Jane Khoo & Rahman Mohamed, ‘Development of Printmaking in Malaysia’ in An Outline of the

Development of Social Realist Woodcuts in Malaysia, pp. 9-18 (p. 9) (Kuala Lumpur: Krystie Ng, 2020).

Khoo’s and Mohamed’s statement also prompts us to consider the ‘easy circulation’ of prints, as well as its value. Some common misconceptions surrounding prints are that they are easily reproduced, and that it is as simple as running a sheet of paper through a printing press, or stamping it with a woodblock. In printmaking, one is considered a master printer because of their ability to produce many editions without compromising its quality and likeness. Despite its affordable pricing, the value of prints lies in its ability to reach far and wide, that an artist’s message can reach the hands of more than just a solitary collector, and that art can be given another life with each edition printed. In this way, the widespread distribution of prints undermines the culture of exclusivity in local collecting practices, as well as the underestimation of prints as serious art objects. In discussing the link between printmaking and humanity’s natural propensity to share, Juhari writes: “[Printmaking] has its origins in Palaeolithic caves, the kitchens of our mothers, the clothes we wear, our places of worship, and knowledge centres. Printmaking creations aim to spread feelings, art, and information for uniformity of culture. Afterall, is not the concept of sharing a genuine trait and value of humanity?”2

2 Juhari Said (trans. by Dhojee & Sumangala Pillai), ‘Hand Stencils’ in WABAK GoBlock: The Expanded Contemporary Printmaking (Kuala Lumpur: Art Valley Sdn Bhd, 2020), pp. 12-13 (p. 12).

3 Camille Mathieu, “Like @ Sac! Livres d’artistes / French Artists’ Books and the Avant Garde.”Art, Archaeology and Ancient World Library: A Bodleian Libraries blog, 1 October 2018,

http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/sackler/2018/10/01/livres-dartistes-french-artists-books-and-the-avant-garde/, (para. 3).

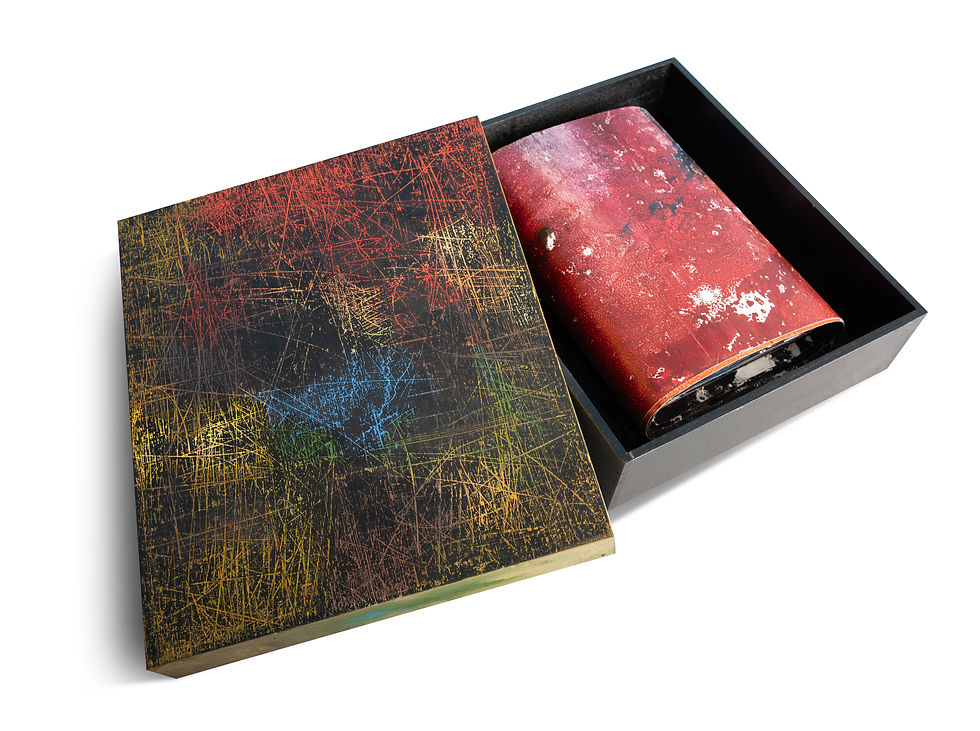

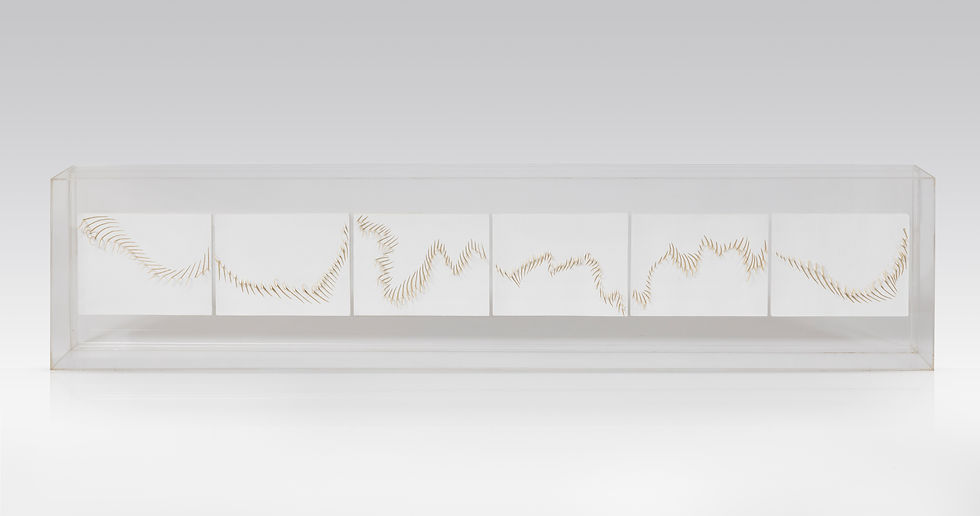

GoBlock: Senibuku aims to highlight the expanded practice of contemporary Malaysian printmaking with a focus on artists’ books. These one-of-a-kind editions are works of art in the form of books. Art historian Camille Mathieu explains, “the artist’s book is a rather hybrid form. It turns a story or a poem into an object; it lends the weight of materiality to the metaphorical weight of narrative. It is necessarily a collaborative effort: author, artist-illustrator, typesetter, printer, editor, publisher—all of these people have a hand in producing the final product.” Each artist in this exhibition embodies a sense of each of these professions with enthusiasm, challenging themselves to engage in practices outside their own. This group exhibition features the works of GoBlock members Juhari Said, Faizal Suhif, Samsudin Wahab, and Fadli Mokhtar alongside other multidisciplinary artists invited by GoBlock. These invited artists are Agnes Lau, Bibi Chew, Haafiz Shahimi, Haslin Ismail, Phuan Thai Meng, and Rizo Leong. With both traditional and alternative approaches to printmaking, GoBlock: Senibuku presents an array of techniques including etching, woodblock printing, monoprint, frottage, cyanotype, linocut printing, pyrography, and more. Unified by curiosity, enthusiasm, and the promise of a good challenge, this group of artists explores the conceptualisation, printing, and binding of an artists’ book. As a result, this project has bound together an unconventional library of printmaking, symbolising the collaborative spirit of the Malaysian printmaking community

Comments