COMMUNICATION IN GRAPHIC - PRINTMAKING

- senicetak malaysia

- Sep 12, 2021

- 11 min read

By Long Thien Shih

ORIGINAL PRINT. GRAPHIC ART

The print illustration has been a major means of recording and reflecting the different aspects of man's civilisation since the invention of paper. Like all other artforms, its beginnings were utilitarian in nature. But like all other artforms, it has been taken by the more innovative, the more inspired and the more creative of its practitioners to great heights of aesthetic expression. Again like all other art forms, the point of departure from craft to art seems to have been largely due to the involvement of amateurs who, in approaching the craft with more love than technical skill, leave behind the inimitable mark of their individual genius. The story of printmaking as an artform in Malaysia is no different.

Printmaking in the 1940s

ln 1947, a book known as "Woodcut Prints from the 8 Year War Against The lnvaders" arrived in Singapore from China and caught the attention of many artists in Singapore and Malaya. According Tan Tee Chie, currently lecturing at The Nanyang Academy in Singapore, it was the first time he had seen reproductions of woodcut prints. He and his fellow-students, then young students at the Academy, were so inspired by the content and style of the woodcut prints in the book that they began to experiment with the woodcut as an art form. They had no previous knowledge of or experience in the medium; their tools and materials were improvisations (the triangular blades or chisels, for instance, were made from the metal tubes of umbrellas); their learning process was one of trial and error. But a year or so later, they had their prints published in the local Chinese-language newspapers. Thereafter, wood block prints became a regular feature in the dailies as a supplementary form of illustration.

The popularity of the woodcut illustration among the editors of the Chinese dailies can be traced back to the traditional practice of the newspaper publishing in China at the turn of the century. The birth of modem literature in China was brought about by Lu Shun who advocated the democratisation of reading materials. Literacy in China then was confined to the elite: scholars and members of the lmperial court. Most reading materials were in a language neither readable nor understood by the masses. Lu Shun and the statesmen of the time believed that the modernisation of the Chinese people depended on the dissemination of knowledge and, therefore, literacy. The process of simplifying the written language began with the publication of newspapers using language based on the common linguistic usage of the majority. Pictures and illustrations for these publications were sourced from woodblock print artisans.

The editors of Chinese-language publications in Malaya and Singapore in the late 1940s were immigrant scholars from China. They brought with them the progressive ideas of the "May Four Uprising Movement", spearheaded by Lu Shun and his comrade in China against foreign intrusion. They saw the parallel function that could be served by the woodcut prints produced by local artists, and frequently published these works in their dailies.

For local woodblock printmakers, the daily press was the only outlet for their works: the money paid to them each time their works were published was an incentive to further the art; and the publication of their works denoted a certain degree of recognition for their artistic abilities. It may be said then that the Chinese language newspaper editors of the time became the first patrons of print art in this country.

Tan Tee Chie, Road Builders, Woodcut, 1953

Printmaking in 1950s

As more and more students took up the art of woodblock printing, a woodcut printmakers club was formed in 1955 at the Nanyang Academy, Foo Chee San, Lim Yew Kuan, See Chen Tee and many others were active practitioners of woodcut prints and enjoyed the unreserved support of the local Chinese language dailies.

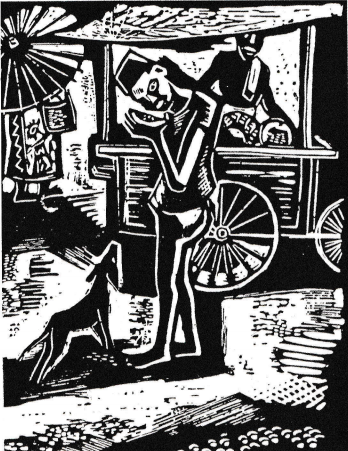

The prints of the era show a spirit and stylistic approach which is similar to that of the pre-and post-war German Expressionists, in particular the works of Kathe Kolwitz (1876-1945). In German the suffering and economic hardships caused by the wars formed the main theme of the printworks. In Malaya and Singapore, we see the same spirit of social consciousness reflected in sympathetic studies of the under privileged. Manual workers, street hawkers, life in the urban slums and in the kampongs were the main subject matter, and remained so right through to the 1960s.

Printmaking in the 1960s

Up to this point in our survey, print art in this country was largely in the hands of locally trained artists inspired by woodblock art from China. If the influence from Europe, in particular Germany, can be detected in their work, this influenced was filtered, so to speak, through China and the Chinese experience. It was not until the 1960s that we began to see printworks by artists from other countries as well as by Malaysian artists who had received their art education abroad, notably Europe and Taiwan.

ln 1963, two artists from Thailand held a joint exhibition at the Selangor Club in Kuala Lumpur. One of them showed a large collection of woodblock prints. At about the same time a Malaysian, who had just returned from Thailand, held at The British Council a show consisting of works he labelled "monotypes". These "monotypes" were in fact impressions obtained from colours rolled onto a hard surface, such as a glass sheet, on which no incision or relief can be made. However, a print image is created when a very thin piece of soft paper is laid on the inked portion of the surface, and pressure is applied with a hard point. Prints of this type have been produced by Seah Kim Joo, T.K. Karan and some others.

ln 1964 Lee Joo-For came back from London with a Master's Degree in Fine Art Printmaking from the London Royal College of Art, and held a solo show of his paintings and prints in Kuala Lumpur. Joo-For may, with justification, claim to be the first Malaysian artist to have dealt with the print medium in a substantial way. Unfortunately, the print art world was soon to lose him to the literary world as he involved himself more and more in that area of self-expression. Latiff Mohiddin is another artist who has made use of the print medium for his art since the early 60s.

Foo Chee San, Fishing Village, Woodcut, 1967 See Cheen Tee, The Creater. Woodcut, 1966

In the meantime, the Woodcut Prints Club at the Nanyang Academy continued to be as prolific as ever. ln 1966 an exhibition of woodblock prints by its members was launched in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. ln addition to the prints, woodblock printing tools and materials were shown, and demonstrations of woodblock printing techniques held. The exhibition attracted large numbers of school children and their teachers, and lino-cut printmaking soon became a popular art medium in schools in the main towns of Malaysia as well as in Singapore.

By and large, however, the 1960s saw woodblock prints becoming a less and less important component of the local art scene. With political independent came new nation-building objectives and economic developments. The editorial policies of the Chinese-language newspaper changed in response to the new political atmosphere. Wood block prints fell out of favour and the local printmaking artists lost their longstanding patrons.

Cheong Soo Peng, Hawkers, Woodcut, 1961

on the social level, abstract, so called "modern art" and non-objective paintings took center stage. Figurative paintings and pictures with social-realistic inclinations were considered outdated. Abstract painting got bigger and bigger in size, and printworks, always limited by the size of the block, had little chance of competing for attention of exhibitions. Oil paintings, batiks and watercolors took the best part of sales; printworks, generally given less show space, in less commanding positions, elements in paintings, dropped in value. Painters who had occasionally experimented with printworks abandoned the medium altogether. Even Lee Joo-For, both a proponent of the "new" art as well as a printmaker, submitted to the overwhelming trend.

Print-related techniques survived in the mainstream of Malaysian art mainly as decorative , in Singapore, Soo Peng applied crumpled paper to texture his inkworks on rice paper. Many of his disciples did the same with a variety of styles and techniques. Textures and patterns from natural materials, such as dried leaves, as well as paper cut-outs were frequently employed. But essentially the printable properties of the print medium were rarely expressed as print per se; printmaking had become a subordinate element for the other visual art forms.

It was not until towards the end of the decade that printmaking as an artform in its own right received a new impetus. In 1968 a Malaysian who had studied at the ATELIER 17, founded by Sir William Hayter in Paris, launched an exhibition of 40 prints of etchings by ATELIER artists at the Samat Gallery in Kuala Lumpur. ln addition to the 40 etchings, the exhibition also displayed 30 prints by the Malaysian artist. For the Malaysian public it was only the second major exhibition devoted exclusively to printworks that they had ever seen.

Printmaking in the 1970s

In 1970 the MARA lnstitute of Technology set up a prints workshop as supplementary facilities for students in its School of Ad and Design. lt was then the only institution of higher learning in Malaysia where the study of printmaking was available. Lecturers as well as students began exploring its potential, and they form the main core of printmaking artists in the country today.

A few years later the Universiti Sains Malaysia in Penang set up a more ambitious prints workshop in the Department of Humanities. The workshop included facilities for lithography, etching and photo-serigraphy. But despite the better facilities, not a single printmaker has emerged from that establishment in these last 20 years since its formation. The main pool of Malaysian printmakers continue to be graduates from the MARA lnstitute of Technology who, like their fellow-graduates from USM, tend to use as their basic techniques the etching and serigraphy.

Meanwhile, more scholarship-funded students pursuing degree courses in Western Europe and America were returning home. Among them are some persistent printmakers who were not only proficient in printmaking but were also active participants of international prints exhibitions. Malaysian printmakers are frequently represented in the Tokyo lnternational Prints Biennale Exhibition (since 1969), the British Print Biennale (since 1970), and the Paris Biennale d'Estampes, to name a few. Representation at these international exhibitions have undoubtedly helped to recharge enthusiasm for printmaking and more art students are are taking up the discipline to complement their wherever facilities are available in the colleges. Unfortunately, this enthusiasm does not survive very long, most of them revert to painting soon after graduation and stay away from printmaking altogether.

The decline in printmaking in the 1970s was evident in the scarcity of prints exhibitions by local artist. Most exhibitions exclusively devoted to prints or graphic art, as it is sometimes called, were brought in by foreign cultural missions. The British Council, the Lincoln Resource Center, the Goethe Institute, the French Embassy and the Japan Foundation were particularly involved in this area.

The low level of public patronage is another indicator of the general lack of interest in printmaking. Throughout the 1970s, the general art scene in Malaysia was highly active and buoyant, characterised by frequent private and corporate acquisition of art works and generous corporate sponsorship of art exhibitions and competitions. The situation for printworks was less rosy. Sale of printworks and sponsorship of prints exhibitions and competitions remained marginal.

Despite the lack of incentives and encouragement, the art of printmaking in Malaysia did not die out. On the whole printmakers are persistent lot, For every artist who left the printmaker's workshop for the more lucrative painter's studio, there would be a bunch of newcomers moving up to take his place in the forefront of printmaking, injecting new life into the age-old discipline with innovative and inspired experimentations.

Printmaking in the 1980s and 1990s

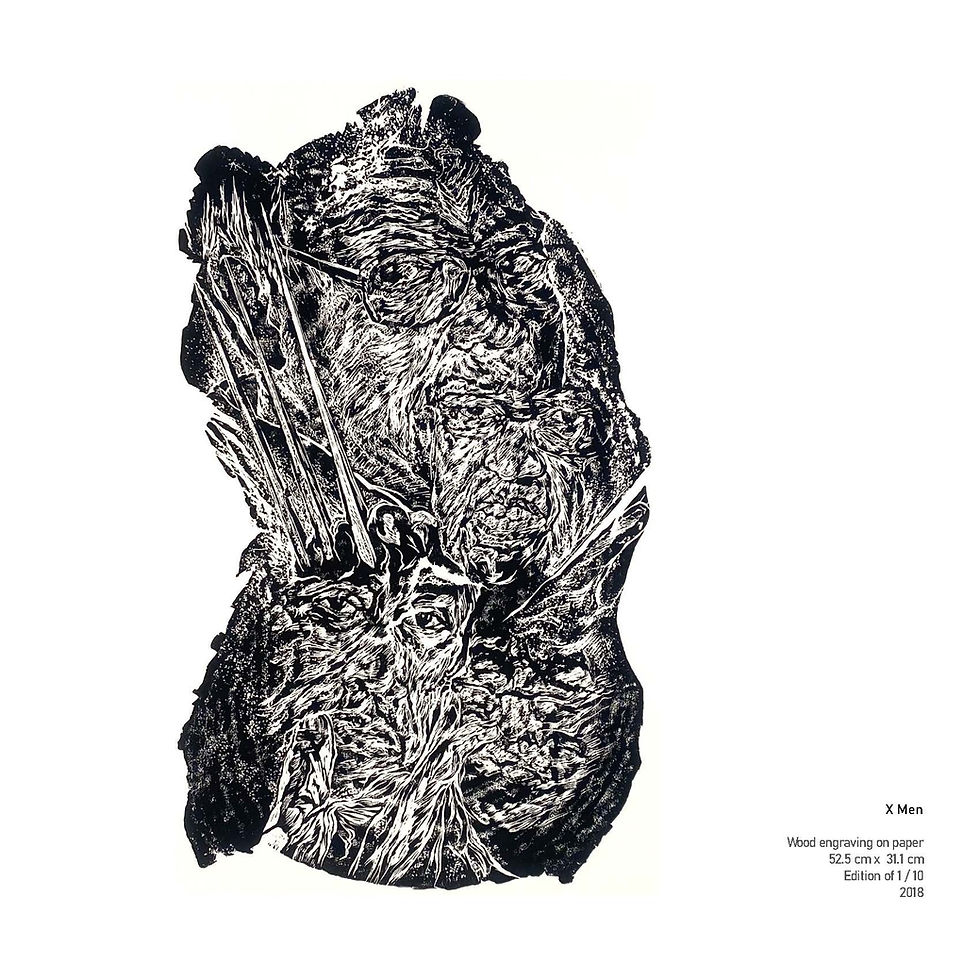

Since the late 1970s, printmaking as a medium of aesthetic expressions has taken many new and diversified routes. During the last 35 years there has been a great flood of imagery from the printmaking centers of the world. It is inevitable that our artists and printmakers would have been exposed to the symbols, codes and visual vocabularies of these external sources, and that these visual elements would have been absorbed, filtered and adapted, to deal with the complex social and cultural phenomenon of Malaysian society. In the hands of innovative artists, the print medium became a dynamic extension of their creative explorations of artistic truth and expression.

Symbols, codes, specific as well as unspecific elements of a uniquely Malaysian character are incorporated in printworks by our artists in the last decade or so. In 1960s, artists were more concerned with the internationalism of abstract expressionism. In the 1970s they were involved in mainstream pop-culture experimentations with overtones of oriental philosophy and western-inspired, trendy avant-gardism. But beginning with 1980s there has been greater awareness of more sober issues related to ecology, ethnic cultures, traditional roots and religious revaluations. So we find that religious dialectics, calligraphical systems, traditional motifs, ethnic folk symbolism and pastoral nostalgia form a significant part of the part of the new subject matter of Malaysia art in general.

The printmakers' allegiance to these issue seem, however to be less dogmatic and, to some extent, even casual. With few exceptions, there is no widespread evidence of these themes in Malaysia graphic art in the 1980s and 1990s. This may due to the small number of printmakers in the country; there are just not enough examples of their output on these themes to evince profound conclusion.

The outlook for printmaking in Malaysia.

ln trying to assess the future of printmaking in this country. One has to look back at the past. lf we are to predict a prolific growth for the artform, we shall have to understand why it has to this very day remained in the background of the Malaysian art scene.

The most impactful reason for the slow growth, or non growth of the art form is the lack of understanding about the artform. There is an unquestioning assumption among the Malaysian public that the value of a work of art lies in its uniqueness; that any work of art that can be replicated (as opposed to duplicated) must be of less or no worth. There is, in fact, a confusion between original art printworks and prints of original works of art. The basic but crucial difference is that in a printwork, the artist is personally involved in the printing process, and the making of the printing plate itself, whereas in the case of a printed reproduction of a work of art, the printing process lies entirely in the hands of a commercial printer who merely photographs the original work and reproduces it on another medium.

This general misconception has led to the relative lack of public sponsorship of printmaking as an artform. Exhibitions are few and far between; competitions, when they are held, are judged by anyone, it seems -painters, sculptors, corporate executives, lawyers, accountants, architects, even language teachers - BUT a printmaker. This practice is hardly conducive to the development and growth of printmaking as an art. lt would be unthinkable not to have a guitarist as a judge in a guitar-playing competition; unbelievable if a painter were asked to judge a music competition. So commonsense would suggest that be included on any panel of judges for a printmakers' competition. The lack of public support and corporate sponsorship has left the printmaking artist to struggle alone and unaided in what is essentially a highly specialised and expensive artform. To create a printwork, one has to first acquire the techniques of printmaking, which is not widely available in this country. Specialized mechanical equipment, tools and materials are hard to get. The sheer financial difficulty an artist faces in acquiring these facilities to set up his own workshop would put off any but the most persistent. Add to this the poor sales of printworks due to the public confusion between the reproduction and the original print and it is no wonder that printmaking remains a medium reserved for the adventurous, innovative, self-motivated, few.

For these few, the outlook of printmaking will always be as it has always been for the dedicated: challenging and full of potential for experimentation and growth. The number of artists/printmakers may be small, their output in printworks may be equally small, but there is no denying the intensity of their creations. On the other hand, it would be fair to say that, as with any other art form, printmaking also has its share of less-than-devoted practitioners. The art of printmaking, however, has just taken root at the ground level in Malaysia and it would be unwise at this early stage to single out the stars from mediocre.

This exhibition is an attempt to present as wide a range as possible of printworks created in Malaysia from the 1950s to the present day (1993), by the devoted and well as the less devoted artists from all levels of our art community. This essay is based on my personal observations and views of the art of printmaking. It is by no means a definitive account of the artform. On the contrary, it is only the first small step in what deserves to be an exhaustive survey of the history of printmaking in Malaysia and of the output of the individual print artists.

It is hoped that this will serve as a springboard for our academicians and art historians to study the situation and perhaps make recommendations for the promotion of this artform. Perhaps then, we may expect a more favourable climate for the growth and development of printmaking in his country. Perhaps by the year 2020. Perhaps....

Long Thien Shih

Essay excerpted from exibition catalog: Communication in Graphic- Printmaking. 1993 National Art Gallery , Malaysia

Comments